Climbing Without Fear

Mar 12, 2021 | 6 min read

Mar 12, 2021 | 6 min read

Want to experience some degree of vertigo? Just watch a video of Alex Honnold climbing. Even his own palms sweat when he watches himself on film. Honnold is, without question, the best free-solo climber in the world. His most recent accomplishment of free soloing the 3,200 vertical free rider route on El Capitan is widely considered the greatest rock-climbing achievement in history. It typically takes seasoned climbers four to five days to complete the route with ropes but Honnold did it in less than four hours without them. The documentary is titled “Free Solo” and it won the Oscar for “Best Documentary Feature” during the 2019 Academy Awards held on Feb. 24. The exciting part which many people agreed to is that his fingers do not have any more contact with the rock than most of us have with the touchscreens of our phones while his toes press down on to the edges as thin as sticks of gum.

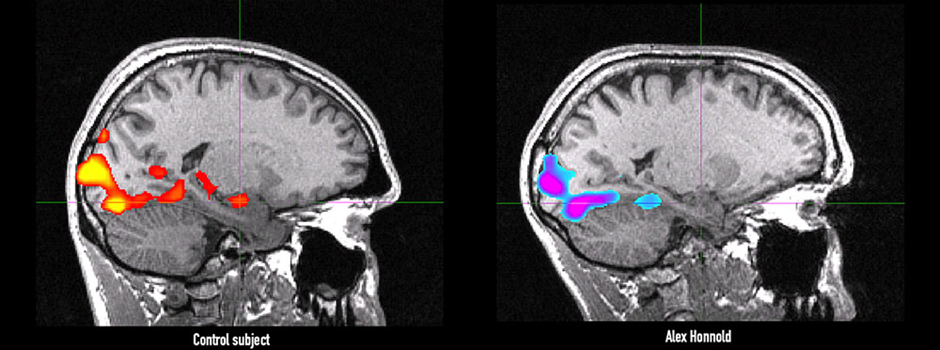

Dr. Jane Joseph, a neuroscientist at South Carolina medical university, wanted to look at Honnold’s brain once she came to know that he doesn’t use any kind of drugs. Honnold happily agreed as he also wanted to gain a better understanding of what makes him tick. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scanner that measures brain activity by detecting any changes associated with the blood flow was used for the study. Dr. Jane is one of the first people to perform fMRIs on high sensation seekers. She saw the possibility of a unique typology in his brain. She put him in the super sensation seeker category - those who will pursue experiences at the outer limits of danger yet can tightly regulate their mind and body’s responses to them. She thought that this could be because of the absence of the amygdala, known as the brain’s fear centre. The amygdala sends information up the line to the higher processing centres in the brain’s cortical structures, where it is translated into the conscious emotion we call fear. In the scan images, surprisingly, they could find a healthy amygdala. Later inside the tube, Honnold was made to look at a series of about 200 images that flicked past at channel surfing speed. Ordinary people get disturbed or excited by those photographs as it included corpses with their facial features bloodily reorganized; a toilet choked with faeces; a woman shaving Brazilian style; two invigorating mountain-climbing scenes, etc. But his response to these were, “What? Was that supposed to do something for me?” Joseph also used a control subject — a high-sensation-seeking male rock climber of similar age to Honnold. Like Honnold, the control subject had also found the scanner tasks to be utterly unstimulating. Yet, in the fMRI images with brain activity indicated in electric purple, the control subject’s amygdala might as well be a neon sign, whereas Honnold’s is grey. He showed zero activation.

Figure 1. Scans compare Hannold's brain (right) with a control subject's (left).

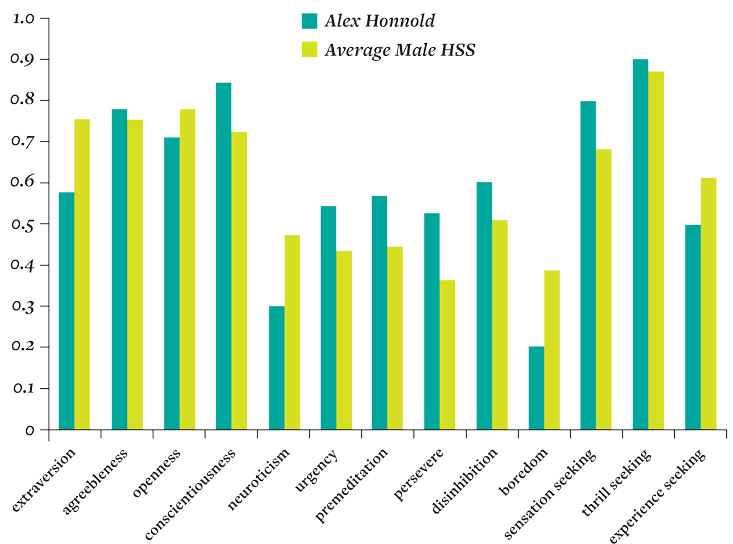

Figure 2