Gene Time Bomb Hurt Mammoths

Dec 17, 2020 | 3 min read

Dec 17, 2020 | 3 min read

Woolly mammoths, Mammuthus primigenius, were among the most populous large herbivores in North America, Siberia, and Beringia (the area bounded to the west by the Lena River in Russia and to the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada) during

the Pleistocene (The most recent ice age) and early Holocene. Warming climates and human predation led to extinction on the mainland roughly 10,000 years ago but the lone isolated island populations persisted out of human reach until roughly

3,700 years ago when the species finally went extinct.

In 2015, two complete high-quality high-coverage genomes were produced for two woolly mammoths. One specimen is derived from the Siberian mainland at Oymyakon (currently the coldest inhabited place on Earth), dated to 45,000 years ago, from

a time when mammoth populations were plentiful, with an estimated effective population size of approximately 13,000 individuals. The second specimen is from Wrangel Island off the north Siberian coast with an estimated population of only 300

individuals. The sample is from 4,300 years ago and represents one of the last known mammoth specimens.

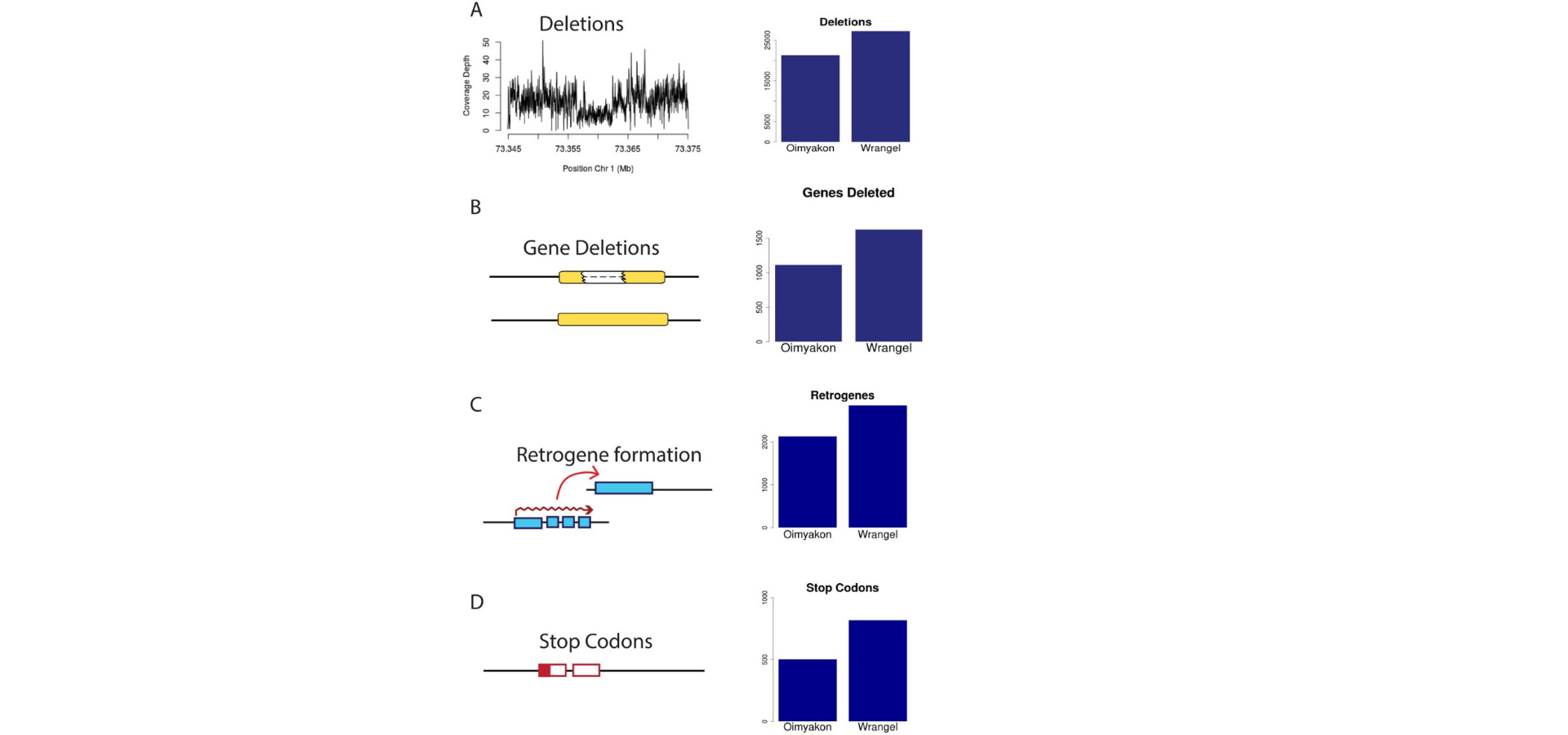

Comparing these two genomes with each other and one Indian elephant specimen the researchers were able to identify retrogenes, deletions, premature stop codons, and point mutations found in the Wrangel Island and Oymyakon mammoths.

The changes found:

Excess of amino acid substitutions and stop codons: All SNPs in both the mammoth genes were identified and also compared to the Indian elephant. With the help of the data, they were able to find that there was a significant increase in the

number of heterozygous and homozygous non-synonymous changes relative to the synonymous changes in the Wrangel island compared to that of the Oymyakon region. To widen the gap further, the number of premature stop codons in the Wrangel island

were significantly greater than that of the Oymyakon region. They observed a difference of around 40 truncated olfactory receptors and 1 vomeronasal receptor pseudogenized in both the mammoths with the Wrangel Island having an excess of

pseudogenized olfactory genes and odorant-binding receptors.

Deletions: The number of deletions too in the Wrangel Mammoths are greater than the Oymyakon Mammoths and this accounts for both hemizygous and heterozygous deletions. One of the major deletions noticed was the hemizygous deletion in the

Wrangel Mammoth which removed the entire gene sequence at the FOXQ1 locus. The FOXQ1 knock-outs in mice are associated with the satin coat phenotype. This phenotype results in translucent fur but normal pigmentation due to abnormal development

of inner medulla of hairs and is caused due to two independent mutations. If the mammoths exhibited the same phenotype it would result in translucent hair and a shiny satin coat.

Retrogene formation: Reterogenes are processed copies of other genes. This duplication mechanism produces a copy of the parental gene that should not contain introns, and usually does not contain cis-regulatory regions. The Wrangel Mammoth had

almost 1.3 times the retrogenes observed in the Oymyakon Mammoth’s genes. Although these retrogenes are unlikely to be detrimental in and of themselves, they may point to a burst of transposable element activity in the lineage that led to the

Wrangel island individual. Such a burst of Transposable Element activity would be expected to have detrimental consequences, additionally contributing to genomic decline.

Discussion:

Under the nearly-neutral theory of genome evolution, detrimental mutations should accumulate in small populations as selection becomes less efficient. The observed excess of retrogenes, deletions, amino acid substitutions, and premature stop codons

in the isolated island mammoths was expected due to the prolonged isolation and low population size. These results offer genetic support to the nearly-neutral theory of genome evolution, that under small effective population sizes, detrimental mutations

can accumulate in genomes.

The Wrangel population was separated from the mainland Oymyakon population for about 6000 years after the extinction of the mainland population. Prior to extinction, some level of geographic differentiation combined with differing selective pressures led

to phenotypic differentiation on the islandic population.

The genes at the FOXQ1 locus were possibly responsible for protecting animals from cold climates. Putative loss of these genes could compromise this adaptation, leading to lower fitness.

Olfactory receptors evolve rapidly in many mammals, with high rates of gain and loss. The island had different flora compared to Oymyakonand also lacked large predators creating new selective pressures without accounting for the sudden invasion of humans.

Parallelly, a huge number of deletions in major urinary proteins in the island mammoths were observed. Most of these urinary proteins and pheromones play a major role in the elicit behavioral responses including mate choice and social status.

All of these selective pressures, in a way, made them vulnerable to the change in climate and coupled with the invasion of early humans hunting down these massive creatures might have led to their extinction.

Figure 1. Representation of deletions, gene deletions, retrogene formations and premature stop codons in the Oimyakon and Wrangel mammoth population. Relative occurences of these elements is depicted in a bar graph alongside the schematic.