Do Animals Dream?

June 14, 2021 | 5 min read

June 14, 2021 | 5 min read

Do animals dream? This question has fascinated people right from the times of Aristotle, who noted, “It would appear that not only do men dream, but horses also, and dogs, and oxen; aye, and sheep, and goats, and all viviparous quadrupeds; and dogs show their dreaming by barking in their sleep."

An obvious obstacle to uncovering the answer to this question is that we can’t really observe another living being's dreams, at least not yet. Nor can an animal let us know about its dream. Despite this, scientists have uncovered some convincing, albeit, indirect evidence suggesting that animals do, in fact, dream. This was done through mainly two approaches, the first by simply observing their physical behaviour during the various phases of the sleep cycle and the second by studying their brain activity patterns.

In humans, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is characterized by the random rapid movement of the eyes, increased electrical activity in the brain, and the propensity of the sleeper to dream vividly. In the last few decades, scientists have identified REM sleep in a wide range of mammals and birds. The pattern of electrical activity in the brains of these animals during REM sleep is similar to that of humans, which suggests that it is highly likely that animals may be dreaming too.

REM sleep is often accompanied by low muscle tone throughout the body. Epidemiological studies revealed that several people around the world act out movements from their dreams during REM sleep. This led researchers to the idea that inducing a similar state in animals may provide insights into how animals dream. In a study as far back as 1959, a team of scientists generated changes in the brains of cats to impair the pathways responsible for inhibiting movement during REM sleep. The results were somewhat astonishing. They observed that the sleeping cats arch their backs, swatted their paws and bit at imaginary objects. Their heads were often raised, which seemed like they were watching unseen objects, all while deep asleep. These movements bore an incredible resemblance to their movements while hunting prey, which led them to conclude the cats were dreaming of catching their prey.

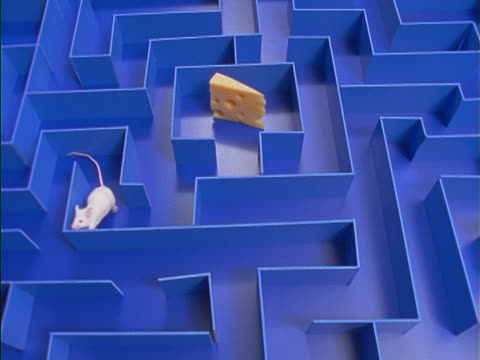

In more recent years, several studies worldwide have tried to find more consolidated proof for the existence of dreaming in animals. Scientists compared the brain patterns of rats trained to run through a maze during their time in the maze and during REM sleep. Interestingly, they found the brain patterns to be so strikingly similar that they could pinpoint and identify the exact zone of the maze the rats were “dreaming” of during their sleep. These results are concordant with observations in humans, where physical spaces like mazes that are frequently encountered, are encoded into the long term memory during REM sleep. A similar study showed that in rats shown food right before bedtime, their brain patterns actually map out how to get to the food.

A study observed the brains of zebra finches, a bird species from Central America, widely known for being loud and boisterous singers. Researchers probed the brains of young birds as they were learning the melodies. They were able to characterize the firing pattern of neurons and the corresponding musical note produced by piecing together the electrical patterns of the neurons. Out of curiosity, they also probed the brains of the birds as they were asleep. Astonishingly, the firing pattern resembled the different musical notes of their song. They concluded that the birds were practising their songs even in their sleep.

Over the years, the evidence for the prevalence of dreams in animals has indeed become more compelling. The physiological and behavioural features of dreaming, similar to humans, have been clearly observed in several animals. However, at this juncture in science, we are still unable to fully understand the extent of dreaming in animals, although it’s always fun to wonder what might be going through the minds of our pets during their slumber.

Figure 1. An experimental cheeseboard maze used in behavioural assays in mice. Brain activity patterns of mice trained to run in such mazes during REM sleep was found to be strongly similar to their time in the actual maze.

Figure 2. Zebra finches

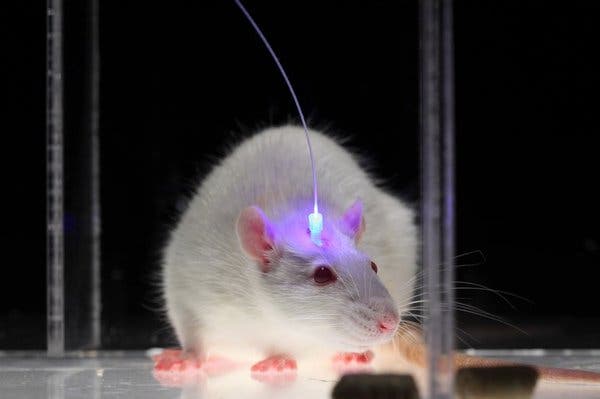

Figure 3. An experimental set-up where optogenetics has been utilized to study brain activity patterns in mice.