T-Cell Transfer Therapy

June 14, 2021 | 3 min read

June 14, 2021 | 3 min read

T-cell transfer therapy is a kind of immunotherapy that fortifies the patient’s immune system in order to attack cancer better. There are two major kinds: tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) therapy and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. Both involve collection of immune cells, proliferation in the lab, and then putting them back into the patient’s body.

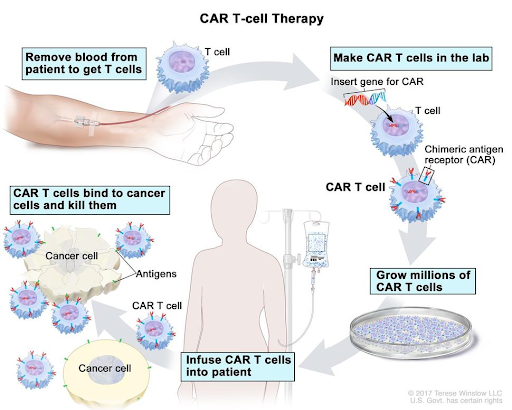

TIL therapy uses T-cells that have penetrated the stroma of the tumour. The logic is that immune cells near the tumour have already shown the ability to recognise tumour cells. They are chosen based on their tumour-specific antigen reception. This method relies on tumour biopsies, after which DNA sequencing helps identify the mutations found in the cancer. These mutated neoepitopes (cancer-specific peptides) are inserted into antigen-presenting cells, then co-cultured with TILs to find those that best recognise the peptides. Giving the body large numbers of lymphocytes that react best with the tumour can prove to be effective in recovery. It’s darkly satisfying to know that the specific mutations of the cancer are what help in treatment. This kind of therapy has proven effective against melanoma, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and bile duct cancer in preliminary studies. Unfortunately, it has a side effect called capillary leak syndrome, in which proteins leak out of capillaries and flow into surrounding tissues, lowering blood pressure dangerously.

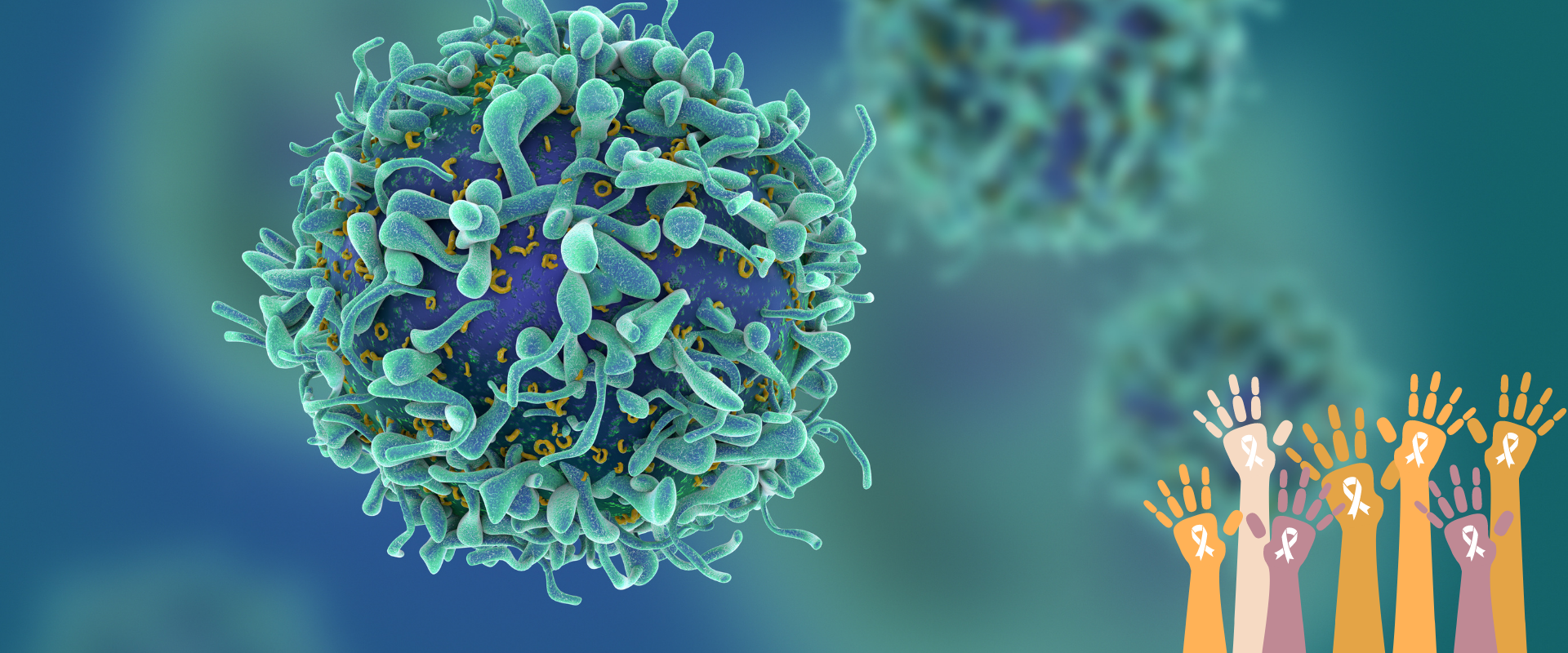

In CAR T-cell therapy, T-cells taken from the patient’s blood are inserted with a gene for a special receptor that binds to a specific protein on the patient’s cancer cells. Large numbers of these modified T-cells are grown in the laboratory and then infused into the patient. This man-made receptor is called a chimeric antigen receptor. Since different cancers have different antigens, the CAR for each is specific. This is used to treat some types of blood cancers, and is being studied for other types. However, they can have a serious side effect called cytokine release syndrome. As the name suggests, it involves the release of large amounts of cytokines, which are immune compounds, into the blood. This can cause fever, nausea, low blood pressure and can impede breathing, among other effects. Sometimes, the CAR T-cells may recognise normal cells instead of cancer cells, which has disastrous consequences.

These methods of immunotherapy are still being refined, and they are far from perfect, but they are a ray of hope where there once was none, and that is the greatest victory of all.

Figure 1. CAR T-cell therapy is a type of treatment in which a patient's T cells (a type of immune cell) are changed in the laboratory so they will bind to cancer cells and kill them.

Figure 2. Steps involved in TIL T cell therapy.