Anabolic Window

September 13, 2021 | 6 min read

September 13, 2021 | 6 min read

Drenched from the resistance training, you stand at the threshold, glancing anxiously at the wall clock in your gym. It’s 7:00 a.m. You gulp down your protein shake and hit the showers. Fancy some poached eggs for breakfast to start your day? Too late. You’ll never make it to a diner before 7:30. Your anabolic window is closing in, teasing the expanding chasm in your belly. What can you do? Can’t argue with Broscience, can you? Many fitness enthusiasts, particularly bodybuilders, believe that by missing the narrow crunch time post-workout, their body loses all the hard-earned ‘gains’. But is there any truth behind this belief?

After strenuous exercise, the body is said to be in a ‘catabolic state’, marked by hyperinsulinemia, depletion of glycogen stores in the muscle and liver, and a spike in cortisol and catabolic hormones, which persist until there is nutrient intervention. In such a state, the skeletal muscle is highly receptive to nutrient intervention, the occurrence of which shifts the body to an anabolic state and reverses the above-mentioned conditions. The ingestion of carbohydrates produces a large insulin response, thereby inhibiting muscle protein breakdown. GLUT-4 is upregulated after exercise, which allows for greater carbohydrate utilization, by acting as a glucose modulator across the cell membrane. There has been evidence both for and against the importance of nutrient timing. In order to gain insight into the reality of this anabolic window, it is only logical to try and piece together snippets of research assembled from famous papers over the years.

Ivy and Ferguson-Stegall's ‘Nutrient Timing' and Lemon, Berardi and Noreen's paper, among others, emphasize the importance of ingesting proteins/EAA and carbohydrates “closely associated with exercise training sessions” to facilitate a speedy recovery and enhance both muscle growth as well as exercise performance. The former states: “Delaying supplementation for 2 hours reduces the rates of muscle glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis by 50% or more and occurs despite normal increases in blood glucose and insulin levels." While a huge body of similar work is enough to convince almost about anyone that their magic 30-minute slot has merit, there is a sizable amount of research refuting these claims.

Hoffman(2) found no changes in strength, power, or body composition in resistance-trained men. Erskine(3) also found no significant improvement in training adaptation. However, in both, nutrient consumption was not controlled after RT sessions. Verdijk(4) too published his findings in a paper entitled: ‘Protein supplementation before and after exercise does not further augment skeletal muscle hypertrophy after resistance training in elderly men’, the drawbacks of which, were touched on by (1).

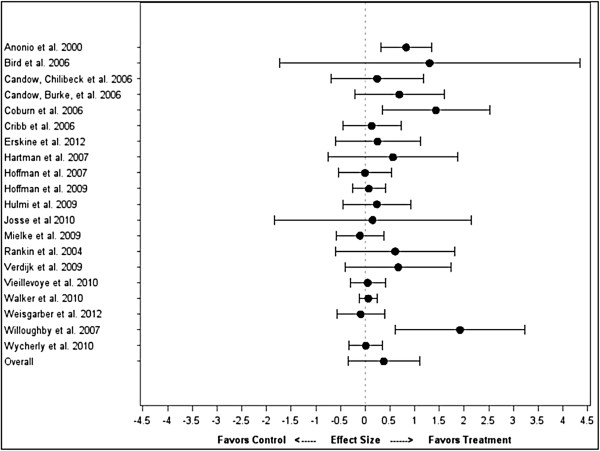

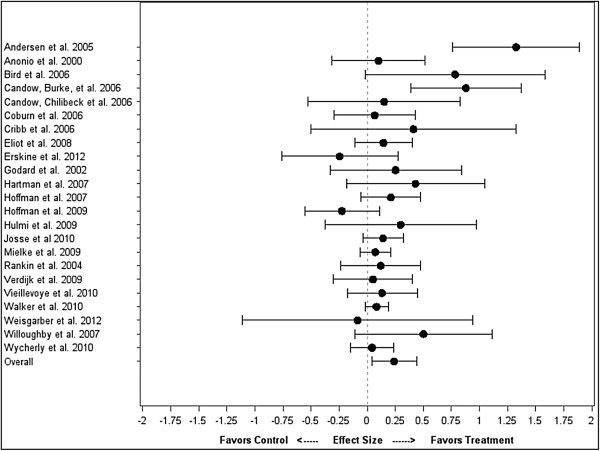

Studies with matching inclusion criteria and statistical data are too few to either demerit or confirm the existence of such a window. Although it may seem that every new advancement seems to contradict the one preceding it, the journey hasn't been inconclusive. The meta-analysis by Schoenfeld, Aragon and Krieger is one such trial that has offered an escape route from the rabbit hole of antithetical arguments.

In their randomized controlled trial, the treatment group received ~6g of proteins/EAA pre-/post-RE while the control did not consume any protein for 2 hours pre-/post-workout. The result: “the effect of protein timing on gains in lean body mass were small to moderate.”, and these small effects disappeared on controlling the co-variates in an expanded regression analysis. Although the ‘Ceiling effect’ had not been attributed for, both the reduced models, for strength and hypertrophy (analyzed separately) showed no significant difference between control and treatment groups.

Consuming protein within 3 hours, 1 hour and in the supposed window, all yield the same results. Hence, it wouldn’t be too far from the truth to say that such a window does not exist. Bulking requires a calorie surplus. For positive results, the rate at which MPS takes place should exceed the rate at which muscular degeneration occurs. So, instead of focussing on immediate post-workout nutrient intake, one should strive to tick all the boxes in the daily checklist of all necessary macronutrients and micronutrients. Consuming a mixed macronutrient meal (1) at regular intervals, interspersed during the day ensures a continuous, sustained release of amino acids. MPS (muscle protein synthesis) response from such a meal lasts for around 3-4 hours, and the high level of amino acids and glucose in the body during this period gives no reason to load up on proteins again if a mixed meal has already been consumed pre-workout. Replacing a healthy meal with supplements may not be the best decision, although one mustn’t discredit them completely. In cases wherein one has been exercising in a fasting state or is unable to eat a complete meal at that time, a scoop of whey or any quick-release protein might be a good idea.